Multifetal Pregnancy Reduction in Halacha

Multifetal Pregnancy Reduction

The contents of the shiur appear on the page below. The shiur and a variety of additional materials are also available for download in PDF format:

Shiur & Appendices in PDF Supplemental Sources in PDF

*********************************

Table of Contents

| Section | Title | Page |

| I | Introduction | 1 |

| II | Two approaches to potentially permit multifetal pregnancy reduction | 2 |

| III | The “obstructed labor” situation: When can the mother be saved at the expense of the fetus’ life? | 7 |

| IV | The “fugitive” situation: When can the townspeople save themselves at the expense of the fugitive’s life? | 9 |

| V | Reason for the difference within the two obstructed labor and the two fugitive situations (Approach 1) | 11 |

| VI | Reason for the difference within the two obstructed labor and the two fugitive situations (Approach 2) | 14 |

| VII | Application of אין דוחין נפשׁ מפני נפשׁ and רודף דין to the multifetal pregnancy situation | 25 |

| VIII | Possible approach to permitting multifetal pregnancy reduction based on Rav Moshe Feinstein’s explanation of the רודף דין | 27 |

| IX | Conclusion | 32 |

| X | References | 34 |

| Appendix A | The “Fugitive” Situation in the Tosefta and Yerushalmi Terumot, as Explained by Rav Moshe Feinstein | 35 |

| Appendix B | Rashi’s View of the “מאי חזית” Logic in the “Coerced Murder” Case, as Explained by Rav Moshe Feinstein | 43 |

| Appendix C | Medical Facts Relevant to Multifetal Pregnancies and Multifetal Reduction | 50 |

| Appendix D |

אין דוחין נפשׁ מפני נפשׁ: Rav Moshe Feinstein’s Explanation of Rashi |

LI |

לעילוי נשמת אחי ורבי הרב ישראל יוסף אליהו בן ר׳ טוביה הלוי זצ״ל

ולעילוי נשמת ר׳ יצחק בן יהודה ע״ה

Note: This Shiur it is not intended as a source of practical Halachic (legal) rulings. For matters of Halacha (practical details of Jewish law), please consult a qualified Posek (rabbi).

Table of Sources - מקורות

| Source No. | Pages No. | Source | Source Subject |

| 1 | 2 | גמרא, מס׳ סנהדרין, דף עד ע״א | יהרג ואל יעבור

be killed rather than transgress |

| 2 | 3 | גמרא, מס׳ יומא, דף פב ע״ב | יהרג ואל יעבור - לא תרצח |

| 3 | 4 | רש״י מס׳ סנהדרין, דף עד ע״א | יהרג ואל יעבור - לא תרצח |

| 4 | 4 | ויקרא פרק יח: ה ;יומא דף פה ע״א | The “וחי בהם”-dispensation |

| 5 | 6 | משנה, מס׳ סנהדרין, דף עג ע״א | דין רודף |

| 6 | 7 | משנה, מס׳ אהלות ,פרק ז׳: ו׳ | “Obstructed Labor” Situation |

| 7 | 8 | גמרא, מס׳ סנהדרין, דף עב ע״ב | “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” |

| 8 | 8 | מנחת חינוך, מצוה רצו | יהרג ואל יעבור - לא תרצח |

| 9 | 9-10 | תוספתא, מס׳ תרומות, פ״ז ה״כ | “Fugitive” Situation |

| 10 | 10 | ירושלמי, מס׳ תרומות, פ״ח ה״ד | Fugitive Situation |

| 11a-b | 11 | רש״י, מס׳ סנהדרין, דף עב ע״ב

)סמ"ע על שלחן ערוך חושן משפט( |

Obstructed Labor Situation |

| 12 | 12 | חסדי דוד על תוספתא תרומות | Fugitive Situation |

| 13 | 14 | רמב״ם, הל׳ רוצח פ״א, ה״ט | Obstructed Labor Situation |

| 14 | 16 | אגרות משה, חושן משפט ח״ב, סימן עא׳ | Obstructed Labor Situation |

| 15 | 17 | אגרות משה, יורה דעה ח״ב, סימן ס׳ | Fugitive and Obstructed Labor Situations |

| 16 | 17 | ירושלמי, מס׳ שבת, פ״ד ה״ד | Obstructed Labor Situation |

| 17 | 21 | אגרות משה, יורה דעה ח״ב, סימן ס׳ | Obstructed Labor Situation |

| 18 | 21 | אגרות משה, יורה דעה ח״ב, סימן ס׳ | Fugitive Situation |

| 19 | 26 | נשמת אברהם, חושן משפט, סימן תכה׳ | P’sak of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach regarding MPR |

I. Introduction

The focus of this presentation is to explore the Halachic permissibility of performing multifetal pregnancy reduction (abbreviated as: MPR), by applying the teachings of the Talmud (Mishna, Braita and Gemara), post-Talmudic commentators and Poskim (Halachic authorities).

Multifetal pregnancies (abbreviated as: MFP) are associated with several risks including complete pregnancy loss (miscarriage and stillbirth) and very preterm birth (i.e., occurring before 32 completed weeks of gestation) which is often complicated by postnatal mortality (i.e., death after birth) and long-term disabilities. MPR is a procedure performed by obstetricians to reduce the number of fetuses in utero in a MFP, to improve the survival probability of the remaining fetuses. Reducing the number of fetuses leads to improved outcomes, as measured by lower rates of miscarriage, fewer very preterm births and reduced postnatal mortality (see Appendix C, p. 50). MPR is usually performed between 9 to 15 weeks of gestational age. While the preponderance of MFP cases for which fetal reduction was historically performed were triplet or higher-order pregnancies, cases of twin to singleton pregnancy reductions have also been reported.

It is understood that the goal of MPR is to optimize the survival chances of the remaining fetuses in cases where there is a high risk of fetal death without intervention. Yet, since MPR by definition, terminates one or more fetal lives, contemporary Poskim and religious physicians have toiled to understand how Halacha views this predicament. This dilemma falls into the rubric of a general question: Can we end one life to save another life? Generally, taking a life cannot be justified even if it is the sole means for promoting the survival of another life. This principle is described in the Mishna Ohalot as: “אין דוחין נפשׁ מפני נפשׁ” (“Ain Dochin Nefesh Mipnei Nefesh”), which means that we may not push aside one life on account of another life. Nonetheless, in very limited applications discussed below, we are instructed to save a life even if this will lead to the demise of another life. The following discussion describes applications and limits of אין דוחין נפשׁ מפני נפשׁ (which will henceforth be referred to as: “אין דוחין”) and the relevance to the permissibility of MPR.

In the course of this discussion, we will be exploring two different approaches for permitting MPR in cases where the failure to intervene will lead to a high risk of total fetal/neonatal death (i.e., death either in utero or shortly after birth). One approach is derived from the discussion in the Talmud concerning the ruling that one must give up his or her life not to commit murder: “יהרג ואל יעבור” (“Yeherag V’al Yaavor”). Perhaps the basis for the יהרג ואל יעבור ruling, which the Talmud describes as a logical reasoning that one may not presume one life is more valuable than any other life, may not apply in a case of multifetal pregnancy if the fetuses are likely to perish without intervention. If this is true, perhaps the principle of אין דוחין also will not apply under these conditions and MPR may therefore, be permitted. The second approach for permitting MPR is the “דין רודף” (law of the pursuer) which states that the life of a pursued party may be saved at the expense of the pursuer’s life. According to this approach, the fetuses that will be reduced (i.e., aborted) are considered as “pursuers” after the other fetuses. We develop this approach through the brilliant writings of the Gaon and Tzaddik, Rav Moshe Feinstein, זצ״ל, (who was a leading Halachic decisor, Posek, spanning a half-century period in America; henceforth referred to as: “Rav Moshe”) in his magnum opus, Igros Moshe. These approaches are built on two Talmudic cases, the ‘obstructed labor’ and the ‘fugitive’ situations, which will be explained below with different interpretations and their applications to MPR.

II. Two approaches to potentially permit multifetal pregnancy reduction:

Notwithstanding the general principle of אין דוחין, we will examine two approaches that could be applied to permit MPR in certain cases. These approaches originate from two different “life-vs.-life” discussions in the Talmud: 1) the “coerced murder” case; and 2) the “דין רודף” (“Din Rodef”, i.e., the law of the pursuer).

- The “Coerced Murder” case and the “מאי חזית” (“Mai Chazit”) logic:

Definitions:

α: The coerced person: The Jewish person who was ordered by the governor (i.e., the hooligan) to kill another Jew (β) under the threat of being killed if he refused.

β: The hooligan’s target: The person who α was ordered to kill.

A. The Gemara Sanhedrin (Source 1) states that שׁפיכת דמים (murder, i.e., violating the prohibition of לא תרצח, thou shall not murder), is one of the three prohibitions for which one must sacrifice his or her own life rather than transgress. This ruling is called יהרג ואל יעבור - “be killed rather than transgress.”

Source 1: Talmud Bavli - Sanhedrin 74a: Three cases where Halacha requires one to sacrifice his life to avoid transgressing – (יהרג ואל יעבור).

| רבי יוחנן said in the name of רבי שמעון בן יהוצדק: They took a vote and decided in the attic of Nitzah’s home in Lod: Concerning all prohibitions in the Torah, if they tell a person, “transgress and you will not be killed [but if you refuse to do so, we will kill you],” he should transgress and not allow himself to be killed, except for idol worship, illicit relations and murder (for which a person must sacrifice his life rather than transgress). | סנהדרין דף עד עמוד א:

אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן מִשּׁוּם רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן יְהוֹצָדָק נִמְנוּ וְגָמְרוּ בַּעֲלִיַּת בֵּית נִתְּזָה בְּלוֹד: כָּל עֲבֵירוֹת שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה אִם אוֹמְרִין לָאָדָם עֲבוֹר וְאַל תֵּהָרֵג יַעֲבוֹר וְאַל יֵהָרֵג, חוּץ מֵעֲבוֹדַת כּוֹכָבִים וְגִלּוּי עֲרָיוֹת וּשְׁפִיכוּת דָּמִים. |

B. The Gemara (Source 2) states that the Rabbis deduced the Halacha of יהרג ואל יעבור with respect to the prohibition against שׁפיכת דמים (murder), through a logical reasoning (סברא), for which theגמרא recounts a true incident: The governor ordered person “α” to kill person “β” or else the governor would kill α. (This case will henceforth be called the “coerced murder” case). רבא (or רבה) ruled that α must be killed rather than kill β because of the following logic: “מאי חזית דדמא דידך סומק טפי דילמא דמא דההוא גברא סומק טפי” - “Why do you presume that your blood is redder? Maybe that man’s blood is redder.” This reasoning will henceforth be called the “מאי חזית” logic.

Source 2: Talmud Bavli - Yoma 82b: Reason for the יהרג ואל יעבור ruling in the “coerced murder” case: The “מאי חזית” logic.

| From where do we know that a person must sacrifice his life rather than commit murder? It is based on logic (סברא) [as we see from the following incident]: A certain person (α) came before רבא and told him, “The governor of my village said to me, ‘Go kill So-and-so (β), and if you do not [kill him], I will kill you.’” רבא replied to him (α), “Let him kill you and do not kill (β). Why do you presume that your blood is redder [than β‘s blood]? Perhaps the blood of that man (β) is redder.” | יומא דף פב, עמוד ב:

וְרוֹצֵחַ גוֹפֵיה מְנָא לָן? סְבָרָא הִיא. דְהַהוּא דְּאָתָא לְקַמֵיהּ דְרָבָא וְאָמַר לֵיה אָמַר לִי מָרִי דוּרָאי 'זִיל קַטְלֵיה לִפְלָנְיָא וְאִי לֹא קַטְלִינָא לָךְ. אָמַר לֵיה לִקְטְלוּךְ וְלֹא תִּקְטוֹל. מַאי חָזִית דְדְמָא דִידָךְ סוּמָק טְפֵי דִילְמָא דָמָא דְהַהוּא גַבְרָא סוּמָק טְפֵי ? |

C. What is the meaning of the “מאי חזית” logic and how does it dictate the Halacha of יהרג ואל יעבור by שׁפיכת דמים (the “coerced murder” case)? The following two approaches are presented:

i. Approach 1: The “מאי חזית” logic operates from a perspective of uncertainty, i.e., since we do not know whose life is considered more valuable, the uncertainty dictates that one must maintain a passive stance to avoid arbitrarily selecting who should be allowed to live versus who should be killed, even at the pain of his own death (Talmeidai Rabbeinu Yonah, Reference 1; see also p. 45, Source B-2). Rav Nochum Partzovitz (Reference 2) attributes this approach to Tosfot in Sanhedrin 74b.

According to this approach, in cases of MFP where there is a high risk of total fetal/neonatal death, an argument could be made to permit MPR. Since the fetuses that would be reduced (i.e., aborted) via the MPR procedure would likely die anyway if we remained passive, it is not considered selecting them for death and therefore, the “מאי חזית” logic would not apply. This will be discussed further below (see VII-2-C, p. 25).

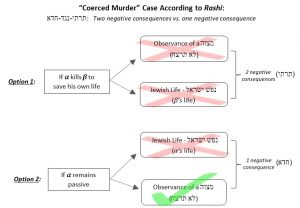

ii. Approach 2: Rashi (Source 3) explains that although the גמרא derives the principle that מצות are pushed aside for the preservation of life from the words “וחי בהם” (Vayikra 18:5, “and he shall live by them”, Source 4), this “וחי בהם-dispensation” does not extend to the prohibition against murder because of the “מאי חזית” logic: If α would murder β to save his own life, the intent of the “וחי בהם-dispensation”, i.e., preservation of a Jewish life, cannot be fulfilled because a Jewish life (β) will be lost through the very violation of the מצוה (i.e., the prohibition of לא תרצח). In the absence of the “וחי בהם-dispensation”, the מצוה must be observed even at the cost of his (α’s) own life. (See Figure 1, p. 5 for a schematic diagram of Rashi’s explanation). Rav Moshe, when discussing this Rashi, adds, “Therefore, we infer [from Rashi] that with regard to this דין [of יהרג ואל יעבור], his (α’s) life and the life of his friend (β) are equal” (Reference 3). Possibly, Rav Moshe inferred the equality of both lives (α and β) from Rashi’s explanation that the intent of the “וחי בהם-dispensation” is negated when the preservation of one life is neutralized by the destruction of another equally valued life (see Appendix B, pp. 43-49, for further aspects of Rashi’s. view of the “מאי חזית” logic, with Rav Moshe’s explanation).

Source 3: Rashi’s explanation of the “מאי חזית” logic: Inapplicability of the “וחי בהם-dispensation” in the “coerced murder” case (Talmud Bavli - Sanhedrin 74a):

רש״י ,סנהדרין דף עד ע״א, ד”ה סברא הוא:

| [The logic is]: α may not push aside his friend (β’s) life which entails two [negative consequences, “תרתי”], a loss of (β’s) life and transgression of an עבירה (i.e., לא תרצח), in order to save himself [from being killed] which would only entail one [negative consequence, “חדא”], a loss of (α’s) life, but he will not transgress (לא תרצח). | שלא תדחה נפש חבירו דאיכא תרתי אבוד נשמה ועבירה מפני נפשו דליכא אלא חדא אבוד נשמה והוא לא יעבור. |

| The Torah only permitted us to violate מצות based on the “וחי בהם-dispensation” because a Jewish life is precious in the eyes of Hashem. | דכי אמר רחמנא לעבור על המצות משום וחי בהם משום דיקרה בעיניו נשמה של ישראל. |

| However, here, regarding [the transgression of] murder, [i.e., if α kills β, the “וחי בהם-dispensation” won’t apply for the following reason]: Since a life will be lost in any event, why should it be permitted to transgress? | והכא גבי רוצח כיון דסוף סוף איכא איבוד נשמה למה יהא מותר לעבור? |

| Who says (literally: who knows) that your (α’s) life is dearer to Hashem than your friend (β’s) life? | מי יודע שנפשו חביבה ליוצרו יותר מנפש חבירו? |

| Therefore, the word of Hashem (לא תרצח) may not be pushed aside. | הלכך דבר המקום לא ניתן לדחות. |

Source 4: Basis for the dispensation to suspend nearly all מצות for the preservation of human life: The “וחי בהם-dispensation” (Vayikra 18:5 and Talmud Bavli - Yoma 85b).

| You shall observe my statutes and ordinances which a man shall do and live by them, I am Hashem. | ויקרא פרק יח: פסוק ה:

וּשְׁמַרְתֶּם אֶת חֻקֹּתַי וְאֶת מִשְׁפָּטַי אֲשֶׁר יַעֲשֶׂה אֹתָם הָאָדָם וָחַי בָּהֶם אַנִי יקוק. |

| Rav Yehuda said in the name of Shmuel: The words “וחי בהם” teach us that he shall live by them (the מצות) and he shall not die by them. | יומא דף פה עמוד ב:

אמר רב יהודה אמר שמואל …וחי בהם ולא שימות בהם. |

Figure 1: Rashi’s explanation of the יהרג ואל יעבור ruling in the “coerced murder” case: The “וחי בהם-dispensation” is inapplicable.

If α would murder β to save his own life (Option 1), there would be two negative consequences: the loss of a life (β’s life) and violation of a מצוה (i.e., transgression of לא תרצח). On the other hand, if α remains passive (Option 2), only one negative consequence would occur: the loss of α’s life, but no מצוה will transgressed. The reason for the “וחי בהם-dispensation” is that a Jewish life (נפש ישראל) is dearer to Hashem than His מצות and thus, He prefers to forego His מצות in favor of preserving a נפש ישראל. However, here, since a life (β) will be lost in end, why should Hashem be willing to forego his מצוה (i.e., why should He allow α to transgress לא תרצח)?

Red X: Denotes the loss of a Jewish life (נפש ישראל) or a violation of a מצוה.

Green check: Denotes the fulfillment of a מצוה.

- Concept of Pursuer - “רודף” (“Rodef”; Source 5):

Definitions:

רודף - Pursuer: Person who endangers the life of a prospective victim.

נרדף - Pursued person: The prospective victim, whose life is endangered by the רודף.

A. A pursuer who attempts to kill a prospective victim is called a רודף. The Torah authorizes the נרדף or anyone else to preemptively take the רודף’s life to save the נרדף. This is called the “דין רודף”.

Source 5: Mishna - Sanhedrin 73a: The דין רודף: Saving the intended victim by killing the pursuer.

| These are to be saved at the cost of their (attackers’) lives: One pursuing his fellow man to kill him … | סנהדרין דף עג, עמוד א:

וְאֵלּוּ הֵן שֶׁמַּצִּילִין אוֹתָן בְּנַפְשָׁן הָרוֹדֵף אַחַר חֲבֵירוֹ לְהָרְגוֹ… |

B. For the purposes of this discussion, we will divide pursuers (רודפים) into two categories:

i. Intentional רודף: This category refers to the classic pursuer who intends to kill or endanger another person. This category may perhaps be expanded to a situation where a person displays blatant disregard for another’s life by engaging in an activity with the awareness that it may result in a loss of life even if his goal is not to bring about someone’s death.

ii. Unintentional רודף: This category refers to a pursuer who has no intention to endanger anyone, but nonetheless unwittingly poses a threat to another’s life. This type of pursuer may be a passive participant in a process that leads to endangerment of another person, without knowledge nor intent of any potential harmful consequences.

C. There are two approaches, as to whether the דין רודף applies only to (permit killing) intentional pursuers or to both intentional and unintentional pursuers.

i. Intentional pursuit only: According to the Dina Dechayei (authored by Rav Chaim Benveniste, Reference 4) and the Minchat Chinuch (authored by Rav Yosef Babad, Source 8, p. 8), the דין רודף only applies to cases of intentional pursuit.

ii. Intentional and unintentional pursuit: According to the Chazon Ish (authored by Rav Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz, Reference 5) and Rav Moshe (Source 15, p. 17), the דין רודף applies to cases of both intentional and unintentional pursuit.

D. According to the position that the דין רודף applies even to unintentional pursuit, in cases of MFP where there is a high risk of total fetal/neonatal death, perhaps it would be permitted to reduce one or more of fetuses based on the premise that they pursue after the other fetuses.This will be discussed further below (see VIII, 2-7, pp. 27-30).

III. The obstructed labor situation: When can the mother be saved at the expense of the fetus’ life?

- Mishna, Tractate Ohalot (Source 6): ‘non-emerged fetus’ ‘partially-emerged fetus’

The above Mishna discusses the case of a woman in mortal danger during obstructed labor. The only way to save her life would be to dismember and remove the fetus. Before the fetus’ head has emerged (henceforth described as the ‘non-emerged fetus’), the fetus should be cut out (i.e., killed) to save his mother’s life. The Mishna’s reason to permit sacrificing the fetus is “because her life takes precedence over his life”. However, after the emergence of fetus’ head (henceforth described as the ‘partially emerged fetus’), we must allow the childbirth to proceed although the mother will die, because of the principle of אין דוחין, i.e., we may not push aside the fetus’ life to save his mother.

Source 6: Mishna - Ohalot 7:6: Obstructed labor case: Source for the permissibility to save the mother at the expense of the unborn fetus.

| A woman who Is having difficulty giving birth (and her life is endangered), we cut the fetus within the womb and remove him limb-by-limb, because her life has precedence over his life. However, if the fetus’ *head has emerged, we do not touch him, because we may not push aside one life on account of another life.

*According to the text in Talmud Bavli - Sanhedrin 72b |

אהלות פרק ז, משנה ו:

הָאִשָּׁה שֶׁהִיא מַקְשָׁה לֵילֵד, מְחַתְּכִין אֶת הַוָּלָד בְּמֵעֶיהָ וּמוֹצִיאִין אוֹתוֹ אֵבָרִים אֵבָרִים מִפְּנֵי שֶׁחַיֶּיהָ קוֹדְמִין לְחַיָּיו. יָצָא *רֹאשוֹ, אֵין נוֹגְעִין בּוֹ שֶׁאֵין דּוֹחִין נֶפֶשׁ מִפְּנֵי נֶפֶשׁ. |

Table 1: Summary of the obstructed labor case. Whose life is spared: the mother or the fetus?

| Case | Description | What is the Halacha? | Whose life is spared? | Reason stated in the Mishna |

| ‘non-emerged fetus’ | Fetus is still totally in utero | Cut out the fetus | Mother | The mother’s life has precedence over the fetus’ life |

| ‘partially-emerged fetus’ | Fetus’ head has emerged during birth process | Remain passive | Fetus | We may not push aside one life to save another life |

- Gemara (Talmud Bavli) - Sanhedrin 72b (Source 7):

In this Gemara, רב הונא states that a child pursuer may be killed to save his prospective victim. רב חסדא posed the following challenge to רב הונא from the above Mishna in Ohalot: Since the Mishna rules that we may not kill the ‘partially emerged fetus’ to save his mother even though he is the cause of her endangerment, it is apparent that the דין רודף is not applied to kill a child pursuer? The Gemara answers, “דמשׁמיא קא רדפי לה התם שאני”– “that (obstructed labor) case is different because she is being pursued by Heaven.” Two explanations of the Gemara’s answer are presented:

A. The Minchat Chinuch (Source 8), who believes the דין רודף does not apply in cases of unintentional pursuit, understands the phrase “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” to mean that, in fact, the ‘partially emerged fetus’ is not considered a רודף because physiology (childbirth), rather than volition, has endangered his mother’s life (per Rabbi Dr. Zalman Levine, Reference 6). Accordingly, the Gemara answers the above question on רב הונא by differentiating between the child pursuer and the ‘partially emerged fetus’, i.e., the דין רודף applies to the former case because the child pursuer intends to kill his prospective victim but not to the latter case because the emerging fetus lacks volition.

B. The explanation of the Gemara’s answer, according to Rav Moshe Feinstein, will be discussed below (VI, 4-6, pp. 14-17).

Source 7: Talmud Bavli - Sanhedrin 72b: Does the דין רודף apply to a child pursuer? Source of the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept.

| רב הונא said, If a child pursues his fellow, (the fellow) may be saved at the cost of the child’s life .... רב חסדא posed a question to רב הונא [from a Mishnah]: “If his [the fetus’] head has emerged we may not touch him for we may not push aside one person’s life on account of another person’s life.” But why not kill the fetus – he is a רודף (pursuer)? [The Gemara answers]: That [obstructed labor case] is different because she (i.e., the mother) is being pursued by Heaven. | תלמוד בבלי סנהדרין דף עב, עמוד ב:

אָמַר רַב הוּנָא קָטָן הָרוֹדֵף נִיתָּן לְהַצִּילוֹ בְּנַפְשׁוֹ. .... אֵיתִיבֵיהּ רַב חִסְדָּא לְרַב הוּנָא יָצָא רֹאשׁוֹ אֵין נוֹגְעִין בּוֹ לְפִי שֶׁאֵין דּוֹחִין נֶפֶשׁ מִפְּנֵי נֶפֶשׁ. וְאַמַּאי רוֹדֵף הוּא? שַׁאנִי הָתָם דְּמִשְּׁמַיָּא קָא רָדְפֵי לָהּ. |

Source 8: Minchat Chinuch, Mitzvah 296: The דין רודף does not apply to unintentional pursuit.

(See Supplement 1, Source 3, p. 52, for a more extensive excerpt from the Minchat Chinuch).

| The Gemara in Sanhedrin states that a child pursuer may be killed to save his prospective victim. The Gemara asked from the Mishna in Ohalot, “... ‘If his head has emerged, we may not touch him because we may not push aside one life on account of another life.’ But - why not kill the fetus – he is a רודף?” The Gemara answered, “that [obstructed labor case] is different because she is being pursued from Heaven.” Hence, the fetus is not a רודף and it is forbidden to save one life by taking another life since [the transgression of] murder is not pushed aside [to save a life]. | מנחת חינוך, מצוה רצו:

דהנה מבואר בסנהדרין שם דאף קטן הרודף ניתן להצילו בנפשו. ומקשה הש״ס ממשנה דאהלות … יצא ראשו, אין נוגעין בו מפני שאין דוחין נפש מפני נפש. ואמאי הא הוי ליה רודף? ומשני הש״ס שאני התם דמשׁמיא קא רדפי לה, ואם כן לא הוי רודף ואסור להציל נפש עם נפש אחר כי שפיכת דמים אינו נדחה. |

IV. The fugitive situation: When can the townspeople save themselves at the expense of the fugitive’s life?

Defintions:

Fugitive: Refers to the individual hiding in the city that the hooligans wish to kill. The hooligans order the townspeople to hand the fugitive over to them.

Townspeople: Refers to the remainder of the people in the city who are ordered by the hooligans to either hand over the fugitive or else they will all be killed.

מסירה: Refers to the act of handing over a Jew to the gentiles.

- The Tosefta in Terumot (Source 9) discusses a case in which a group of people (i.e., ‘townspeople’) are surrounded by hooligans who demand they hand over an individual (i.e., a ‘fugitive’) to be killed or else they will all be killed. The Tosefta and the Yerushalmi - Terumot (Source 10) distinguish between a case where the hooligans designate (i.e., single out) a specific victim to be delivered to them versus a case where they simply demand that the townspeople hand over any person to them. If the hooligans do not designate a specific victim, it is forbidden for the townspeople to hand over anyone even though everyone will then be killed. However, if the hooligans designate a specific victim to be handed over, under specified conditions, the townspeople may hand him over to save themselves. The paradigm presented by the Tosefta is the שבע בן בכרי episode in Shmuel II, Ch. 20. After שבע בן בכרי, a fugitive from justice for leading a revolt against דוד המלך, took refuge in the city Avel, the townspeople delivered him to יואב’s sieging army, thereby saving the lives of all the townspeople who otherwise would have been killed when the army invaded the city. Clearly, שבע בן בכרי was a designated fugitive (and was liable to the death penalty for rebelling) as יואב stated, (ibid, verse 21) “שבע בן בכרי has lifted his hand against the king, against David; give us him alone and I will depart from the city.”

Source 9: Tosefta Terumot 7:20: Fugitive case (Explanation is based on the Eitz Yosef on Bereishis Rabboh, Perek 94).

תוספתא מסכת תרומות פרק ז הלכה כ(See Supplement 1, Source 4, p. 53, for a more extensive explanation) :’

| If a group of people [were accosted by] gentiles who said to them, “Give us one of you and we will kill him; and if not, we will kill all of you,” [the ruling is]: Let them all be killed, and they may not give over one Jewish life to them. | סיעה של בני אדם שאמרו להם גוים תנו לנו אחד מכם ונהרגהו ואם לאו הרי אנו הורגין את כולכם יהרגו כולן ואל ימסרו להן נפש אחת מישראל. |

| But if the gentiles designated someone (i.e., a ‘fugitive’) in the manner that they designated שבע בן בכרי, they should hand him over rather than all being put to death. | אבל אם ייחדוהו להם כגון שייחדו לשבע בן בכרי, יתנו להן ואל יהרגו כולן. |

| רבי יהודה said, when does this apply (i.e., they may not hand him over)? Only if the fugitive is in the exterior [and he can escape] while the townspeople are in the interior [and are unable to escape]. However, if all of them are in the interior since [no one can escape and consequently] they will all be killed, they should hand him over to them rather than all being put to death. | אמר רבי יהודה במה דברים אמורים בזמן שהוא מבחוץ והן מבפנים. אבל בזמן שהוא מבפנים והן מבפנים הואיל והוא נהרג והן נהרגין, יתנוהו להן ואל יהרגו כולן. |

| As it states, “And the woman approached all the people with her wisdom” (Samuel II, Ch. 20). She said to them, “Since he will be killed and you will be killed, give him over to them so that all of you will not be killed.” | וכן הוא אומר ותבא האשה אל כל העם בחכמתה. אמרה להן הואיל והוא נהרג ואתם נהרגין תנוהו להם ואל תהרגו כולכם. |

| רבי שמעון said, so she said to them, “Anyone who rebels against the kingdom of David, is liable to execution.” | רבי שמעון אומר כך אמרה להם כל המורד במלכות בית דוד חייב מיתה. |

- Yet, the hooligans’ designation of a specific victim (in most cases) is not sufficient to permit handing the fugitive over. In the Tosefta (Source 9, third statement), רבי יהודה states that the second requirement for permitting handover (מסירה) is that the fugitive must be unable to escape (‘fugitive without escape capability’) even if they do not hand him over. However, if the fugitive can escape (‘fugitive with escape capability’), it is forbidden to hand him over even though he was designated by the hooligans.

- The permissibility of מסירה is subject to further dispute between רבי יוחנן andרבי שמעון בן לקיש (ריש לקיש) in the Talmud Yerushalmi (Source 10). ריש לקיש maintains that the fugitive must liable to the death penalty (חייב מיתה) in order to permit handing him over, whereas רבי יוחנן believes that even if the fugitive was not liable to the death penalty, it is permitted to hand him over. Refer to Appendix A (pp. 35-41) for an explanation of the positions of רבי יוחנן and ריש לקיש.

Source 10: Talmud Yerushalmi, Terumot 8:9: Fugitive case: Dispute between רבי יוחנן and ריש לקיש.

| We learned: If groups of people, who were traveling on the road, were accosted by gentiles who said, “Give us one of you and we will kill him; and if not, we will kill all of you,” [the ruling is]: Even if all of them will be put to death, they should not hand over [even] one person of Israel. But if the gentiles designated someone, as in the שבע בן בכרי episode, they should hand him over and not get killed. רבי שמעון בן לקיש said, This is providing he is liable to the death penalty like שבע בן בכרי was. But רבי יוחנן said, This applies even if he is not liable to the death penalty like שבע בן בכרי. | תלמוד ירושלמי תרומות פרק ח, הלכה ד׳:

תני סיעות בני אדם שהיו מהלכין בדרך, פגעו להן גוים ואמרו תנו לנו אחד מכם ונהרוג אותו ואם לאו הרי אנו הורגים את כולכם: אפילו כולן נהרגים לא ימסרו נפש אחת מישראל. ייחדו להן אחד כגון שבע בן בכרי ימסרו אותו ואל ייהרגו. אמר רבי שמעון בן לקיש והוא שיהא חייב מיתה כשבע בן בכרי. ורבי יוחנן אמר אף על פי שאינו חייב מיתה כשבע בן בכרי. |

V. Reason for the difference within the two obstructed labor and the two fugitive situations (Approach 1):

- Obstructed labor situation: What is the reason that the mother’s life is prioritized only over the life of the ‘non-emerged fetus’, but not over the life of the ‘partially-emerged fetus’? The Sefer Meirat Einayim (סמ״ע; Source 11b) and the Minchat Chinuch (Supplement 1, Source 3, p.52) take the approach that the unborn (‘non-emerged’) fetus does not have the Halachic status of a living human being, according to the standard interpretation of Rashi who states that “until a fetus emerges into the air of the world, he is not a deemed a ‘Nefesh’ (נפשׁ) – a living being” (Source 11a). As such, feticide does not constitute שׁפיכת דמים (murder) and therefore, his life may be pushed aside to save the mother, just as the imperative to save lives (פיקוח נפש) pushes aside all מצות (other than murder, idolatry and illicit relations). However, once the fetus’ head emerges, since he has the full Halachic status of a living being, killing him constitutes שׁפיכת דמים and therefore, we must remain passive so as not to push aside one life on account of another life.

Source 11a-b: Rashi in Sanhedrin (11a) and the Sefer Meirat Ainayim (סמ״ע) on Shulchan Aruch Choshen Mishpat (11b): Status of ‘non-emerged fetus’ (See Supplement 1, Source 2, p. 51, for full text of Rashi):

| רש״י סנהדרין דף עב׃ ד״ה יצא ראשו:

באשה המקשה לילד ומסוכנת. וקתני רישא החיה פושטת ידה וחותכתו ומוציאתו לאברים דכל זמן שלא יצא לאויר העולם לאו נפש הוא וניתן להורגו ולהציל את אמו. |

This is referring to a woman who is having difficulty giving birth and her life is endangered. The first section of the Mishna states that the midwife extends her hand, cuts him and removes him limb-by-limb. As long as the fetus has not emerged into the air of the world, he is not a נפש (i.e., a life) and it is permitted to kill him to save his mother. |

| סמ"ע על שלחן ערוך חושן משפט סי׳ תכה ס״ק ח׳:

ואף על פי כן, בעודו במעיה מותר לחתכו אף על פי שהוא חי, שכל שלא יצא לאויר העולם אין שם נפש עליו, והא ראיה דהנוגף אשה הרה ויצאו ילדיה ומתו משלם דמי הולדות ואין שם רוצח ומיתה עליו. |

Nonetheless, while he is still in utero, it is permitted to dismember him even though he is alive because there is no name (i.e., status) of a נפש on him before he emerges into the air of the world. The proof is from the fact that one who strikes a pregnant woman aborting her pregnancy, must pay restitution for the fetuses, but there is no name of a murderer or death penalty upon him. |

- Fugitive situation: Why is it prohibited to hand over a ‘fugitive with escape capability’ while it is permitted to hand over a ‘fugitive without escape capability’? The Chasdei Dovid (authored by Rav Dovid Pardo, Source 12) explains this distinction based on the logic of “מאי חזית”. If the fugitive has the capability to escape, the townspeople have two theoretical options: (1) they could either allow the fugitive to escape and they will all be killed, or (2) they could save themselves by handing over fugitive to be killed. This is the standard “מאי חזית” dilemma, i.e., “Why do you presume that the townspeople’s blood is redder than the fugitive’s blood?” Accordingly, the townspeople must remain passive and allow the fugitive to escape. However, if the fugitive has no capability to escape, the “מאי חזית” logic does not apply since he cannot be saved even if the townspeople do not hand him over. Since the entire basis for the Halacha of יהרג ואל יעבור by שׁפיכת דמים is the “מאי חזית” logic, when the “מאי חזית” logic does not apply, i.e., if he is unable to escape, it is permitted to hand him over (See Supplement 2, p.46, paragraph 6a-b, for further explanation of the basis to permit מסירה).

Source 12: Chasdei Dovid on the Tosefta (Source 9): Basis for differentiating between the ‘fugitive with escape capability’ and the ‘fugitive without escape capability’: The “מאי חזית” logic.

(See Supplement 1, Source 5, p. 54, for a more extensive excerpt from the Chasdei Dovid).

| When is it forbidden to hand over even a singled-out fugitive? ... [if the fugitive is in a location where] if the townspeople do not hand him over, they will be killed and he will escape. In such cases, even if the hooligans designated him, it is forbidden to hand him over because of the reason of “מאי חזית” (“Why do you presume that the townspeople’s blood is redder than the fugitive’s blood?”).

However, if everyone is in equal danger, i.e., they all are located in the inner sector … such that if the hooligans would come, they would kill the fugitive along with the townspeople – then, if the hooligans designated him, it is permitted [to hand him over] … because the reason of “מאי חזית” does not apply when they all are in an equal state of danger. |

חסדי דוד על תוספתא תרומות :

במה דברים אמורים שאסור על כל פנים למוסרו? ... שאם לא ימסרו אותו, הן נהרגים והוא נמלט, אז אפילו יחדוהו להם אסור מטעמא דמאי חזית דדמא דידך סומק טפי דילמא דמא דההוא גברא סומק טפי כדאמרינן בעלמא ... אבל אם כולם שוין בסכנה כגון שכולם מבפנים ... שאם יבאו עכו״ם הורגים אותו ואותם, אז אם יחדוהו הוא דשרי ... דהא לא שייך טעמא דמאי חזית וכו׳ כשכולם שוין בסכנה. |

A. This explanation fits well with the opinion of the Minchat Chinuch that מסירה is called “אביזרא דשפיכת דמים” - i.e., an “ancillary form” of murder. Accordingly, just as the ruling of יהרג ואל יעבור by שׁפיכת דמים is based on the “מאי חזית” logic, the ruling of יהרג ואל יעבור by מסירה is also based on the “מאי חזית” logic. Therefore, since the “מאי חזית” logic is inapplicable when the fugitive cannot escape, it is permitted to hand him over.

B. On a deeper level, the Chasdei Dovid’s understanding can be explained as follows: Perhaps the Halacha of יהרג ואל יעבור only dictates that one must remain passive (i.e., in the “coerced murder” case) when only one of the two parties will be killed and the only question is which of the two shall be killed. Since we don’t know whose life is more valuable, the “מאי חזית” logic dictates that we must remain passive rather than arbitrarily choosing one party to be killed. However, since the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ will be killed regardless of which option the townspeople choose, there is no reason to remain passive since we are not choosing any person for death. The only choice is whether to have all the townspeople killed along with the fugitive or to spare them, for which we may argue that “מאי חזית” does not pertain.

Table 2: Summary of Approach # 1 to explain the different rulings in the obstructed labor and fugitive situations:

Based on the position that an unintentional pursuer does not have a status of a רודף1-2.

| Type of Situation | Sub-category | Who will be saved, as a consequence of choosing the ________ option? | Is the active option a de facto selection? who shall live vs. who shall die? | Is the active option considered שׁפיכת דמים (murder)? | Does “מאי חזית” apply to forbid choosing the active option? | How does the Halacha decide?

which option? |

||||

| 3Active | Passive | Yes/

No |

Why | Yes/

No |

Why | Yes/

No |

Why? | |||

| Obstructed labor | ‘non-emerged fetus’ | Mother | Fetus | Yes | By terminating the fetus, we are choosing that the mother, rather than the fetus, will live. | No | Since the fetus is not a ‘נפש’, feticide is not murder | No | “מאי חזית” only applies if the action is considered murder. | Active

(Feticide) |

| ‘partially- emerged fetus’ | Mother | Fetus | Yes | Yes | The fetus now has a ‘נפש’ status | Yes | Passive | |||

| Fugitive | ‘with escape capability’ | Towns-people | Fugitive | Yes | Fugitive will escape if we remain passive | Yes | מסירה is an 2“ancillary form” of murder | Yes | 4“מאי חזית” only applies if the action selects who shall live vs. who shall die. | Passive |

| ‘without escape capability’ | Towns-people | No one | No | Fugitive will be killed even if we remain passive | Yes | No | Active 5(מסירה) | |||

1Dina Dechayai (see Supplement 1, Source 6c, pp. 54-55)

2Minchat Chinuch (Source 8, p. 8)

3The active option is as follows: In the ‘obstructed labor’ situation: feticide; in the ‘fugitive’ situation: מסירה (handing him over).

4Based on the Chasdei Dovid (Source 12, p. 12)

5ריש לקיש maintains that מסירה is only permitted if there is a death sentence against the ‘fugitive without escape capability’.

VI. Reason for the difference within the two fetus cases and within the two fugitive cases (Approach 2):

| This is one of the negative commandments not to take pity on the life of a pursuer. On this basis, our Sages ruled regarding a woman who is having difficulty giving birth (and her life is endangered), that it is permitted to cut out the fetus in utero, either medicinally or manually, because the fetus is considered a pursuer after her to kill her. However, once his head emerges, one may not touch him since we may not push aside one life on account of another life and this is the natural order of the world. | רמב״ם, פרק א הל׳ רוצח ושמירת הנפש, הל׳ ט׳:

הרי זו מצות לא תעשה שלא לחוס על נפש הרודף. לפיכך הורו חכמים שהעוברה שהיא מקשה לילד מותר לחתוך העובר במיעיה בין בסם בין ביד מפני שהוא כרודף אחריה להורגה. ואם משהוציא ראשו, אין נוגעין בו שאין דוחין נפש מפני נפש וזהו טבעו של עולם. |

- According to Rav Moshe Feinstein and the other Halachic authorities who maintain that the דין רודף applies even to an unintentional רודף, both the fetus and the fugitive have the status of a רודף since they (albeit unintentionally) pose a danger to the mother or the townspeople, respectively. Accordingly, the permissibility to kill the ‘non-emerged fetus’ or to hand over the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ is based on the דין רודף. Rav Moshe (Reference 7), as well as Rav Chaim Soloveitchik (Reference 8) and Rav Elazar Menachem Man Shach (Reference 10), derive this approach from the Rambam (Source 13) who states that it is permitted to kill the ‘non-emerged fetus’ because he is considered a רודף after his mother.

Source 13: The Rambam’s view: The fetus is viewed as a רודף after the mother.

- Rav Moshe deduces from the Rambam that a fetus is deemed a living being to the extent that feticide is included under the prohibition against murder (לא תרצח) unless the mother’s life is threatened. If feticide was not included under the prohibition of לא תרצח, it would not be necessary to invoke the דין רודף to authorize saving the mother at the fetus’ expense since all prohibitions (other than the three prohibitions mentioned above) are pushed aside for the sake of saving lives (פיקוח נפש).

- However, according to this view, since intent is not needed to be considered a רודף, the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ should also be considered a רודף and therefore, should be killed to save his mother? What is the basis for the distinction in Halacha between the ‘non-emerged fetus’ and the ‘partially emerged fetus’? Similarly, if the basis for handing over the fugitive is his status as a רודף, why is there a distinction between a fugitive who can escape and a fugitive who cannot escape? In both cases, he endangers the lives of the townspeople and should be handed over to save them?

- To explain Rav Moshe’s resolution of this dilemma, we must present his explanation of the phrase, “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” - “she is being pursued by Heaven,” which the Gemara (Source 7, p. 8) states is the reason the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ must not be harmed even to save his mother. According to Rav Moshe’s explanation, the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept applies equally to the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases. The following is the premise of his explanation:

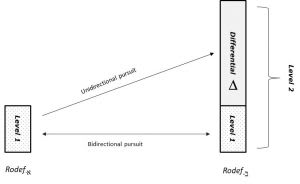

- The obstructed labor and fugitive situations are cases of “bidirectional pursuit”:

- In the obstructed labor situation, the mother and fetus mutually pursue each other;

- In the fugitive situation, the fugitive and townspeople mutually pursue each other.

- The obstructed labor and fugitive situations are cases of “bidirectional pursuit”:

Definition: “Rodef-א” = fetus or fugitive and “Rodef-בּ” = mother or townspeople

Note: The terms “opposing רודפים”, “opposing pursuers” or “opposing parties” denote a confrontation between “Rodef-א” and “Rodef-בּ”.

B. In the obstructed labor and fugitive situations, Heaven has arranged that there would be an “inverse relationship” between the respective survivals of Rodef-א or “Rodef-בּ :

i. If the passive option is chosen, Rodef-א will live and Rodef-בּ will die;

ii. Conversely, if the active option is chosen, Rodef-בּ will live and Rodef-א will die.

C. The reason why the fetus is considered a רודף despite having no intention to pursue or harm his mother, is because his only path to survival is by allowing the birth to proceed, which will cause his mother’s death. Similarly, the fugitive is considered a רודף because his only path to survival is by escaping, which will lead to the death of the townspeople (albeit less directly than the death of the mother via childbirth).

D. One might ask, it is understandable that the fetus and fugitive are considered pursuers (רודפים) since their “arrival on the scene” threatens the lives of mother or townspeople, respectively. However, the mother and townspeople merely wish to defend themselves from the threat imposed on them. If so, how can they be defined as pursuers?

E. Rav Moshe writes (Source 14) that the message of “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” is: Despite the fact that the mother’s life was not endangered until after the “arrival” of the fetus, we do not view the fetus as a unilateral רודף. Rather, Heaven ordained the “arrival” of the fetus with the purpose that both he and his mother would live, and only after this, the situation of danger befell both equally. My limited understanding of Rav Moshe’s explanation is: Since Heaven designed the (obstructed labor or fugitive) situation with an inverse relationship between the respective survivals of Rodef-א and Rodef-בּ , none of which intended to cause harm, therefore, neither party is considered a greater contributor or more responsible for this situation. Accordingly, the same logic that defines the fetus and fugitive as pursuers, also defines the mother and the townspeople as pursuers since their only path to survival is through the death of the fetus and fugitive, respectively.

Source 14: Rav Moshe’s explanation of the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept in the ‘partially emerged fetus’ case.

| 1The גמרא‘s answer “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” comes to refute the contention that the ‘partially-emerged fetus’, who came into existence after his mother, is considered a [unilateral] רודף after his mother since she was not in any danger prior to his arrival in her womb. [The גמרא’s rebuttal is, “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה”, i.e., that on the contrary,] it was Heavenly decreed when the fetus initially arrived here at the inception of her pregnancy, that he also should be here, (i.e., 2his initial arrival was not to pursue, but rather, with the purpose that they would both live). Thus, [it is viewed] as if the pursuit from Heaven befell both equally, whereupon it is only possible for one of them to live and therefore, it is not known who is killing whom.

1This translation is partially in paraphrase form. 2Words in parentheses are from a subsequent section in the same responsum. |

אגרות משה חושן משפט ח״ב, סימן עא׳:

הא דמשני משמיא קא רדפי לה ...היינו שנותן הגמרא טעם על מה שלא נחשב הולד שבא באחרונה לרודף על האם, שהרי כשלא היה הולד במעיה לא היתה מסוכנת. דהוא משום דמשמיא בא שם הולד תחילה כשנתעברה היינו שגם הוא צריך להיות כאן, והוי כבא הרדיפה משמיא על תרוייהו בשוה, דרק אחד מהם יוכל לחיות שממילא לא ידוע מי הורג את מי. |

(See Supplement 2, pp. 80-82, for more extensive excerpts from the Sefer Igros Moshe).

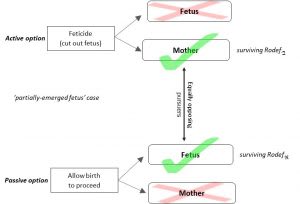

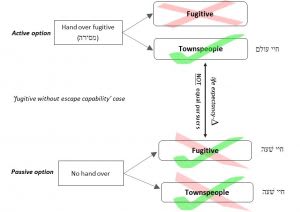

- Thus, the questions in paragraphs 3 and 4D (pp. 14 and 15) can be answered by explaining that the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept tells us that we view the obstructed labor or fugitive situations such that Heaven has arranged that Rodef-א and Rodef-בּ are equal participants in an impasse in which each one’s survival is dependent on the other’s demise, thus rendering both of them equal pursuers after each other. Consequently, we cannot apply the דין רודף to kill the fetus or hand over the fugitive because of the “מאי חזית” logic, i.e., “Why should you presume that Rodef-א pursues after Rodef-בּ more than Rodef-בּ pursues after Rodef-א?” See Source 15; also Figures 2-3, pp. 18-19, for schematic diagrams of the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases, respectively.

- Rav Moshe points out that the Gemara’s answer “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” is identical (or, similar) to an answer in the Talmud Yerushalmi (Source 16). The Yerushalmi attempted to prove that the דין רודף does not apply to a child pursuer, from the prohibition to kill the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ (stated in the Mishna in Ohalot). The Yerushalmi then refuted this proof with the following statement, “שנייא היא תמן שאין את יודע מי הורג את מי” - “That case (of the emerging fetus) is different because you do not know who is killing whom.” Rav Moshe explains the meaning of the answer “שאין את יודע מי הורג את מי” is: “you do not know who pursues whom”, i.e., the mother and the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ equally pursue each other and therefore, the דין רודף cannot be applied because of the “מאי חזית” logic. The Divrei Yissachar (Reference 9) and Rav Shach (Reference 10) also understand that “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” aligns with the Yerushalmi’s answer of “שאין את יודע מי הורג את מי”.

| Therefore, the reason [to permit handing over the fugitive] is because he is considered a רודףbecause the townspeople will be killed on account of him. [One may question] since the fugitive had no intention to pursue them, [the דין רודףshould not apply] because of the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” reasoning [as in the case of] the ‘partially-emerged fetus’? We can answer that this [“משׁמיא קא רדפי לה”] reasoning is only effective [to protect the fugitive] if he could escape and hide. Since he has no intent to pursue, it is only Heaven Who arranged that it is impossible for both parties to survive, for if they spare the fugitive, the townspeople will die and if they spare themselves, the fugitive will die. This is analogous to the obstructed labor case following emergence of the fetus’ head, where he and his mother are considered [equal] pursuers after each other. Although the fetus is the cause [of his mother’s danger], since he has no intent [to harm], therefore, we cannot permit [killing him] on the basis of the דין רודף because of the “מאי חזית” logic – “Why do you presume that the fetus pursues after his mother more than she pursues after the fetus?” | אגרות משה ,יורה דעה ח״ב סימן ס׳, ענף ב׳:

ולכן מוכרחין לומר שהוא מטעם דהוי כרודף כיון שעל ידו יהרגו, ואף שאין כוונהו לרודפם שאם כן הוא רק כמשמיא קא רדפי להו כמז שאמרו בסנהדרין שם לענין עובר שיצא ראשו, צריך לומר שמועיל טעם זה רק באם היה הוא ניצול כגון שיכול לברוח ולהתחבא, שהטעם הוא דמחמת שאין כוונתו לרדוף רק שמשמיא נזדמן כן שאי אפשר להו להתקיים שניהם דאם יצילו את זה ימות זה ואם יצילו את זה ימות זה, כעובדא דהמקשה לילד ויצא ראשו באהלות פ"ז מ"ו נחשבו כרודפים זה את זה אף שהוא הסבה בזה כיון שהוא בלא כוונה אף שהוא הסבה בזה כיון שהוא בלא כוונה ולכן אי אפשר להתיר מטעם רודף דמאי חזית להחשיב את העובר יותר רודף את האם מכפי שהאם רודפת את העובר. |

Source 15: Rav Moshe’s explanation of the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept in the ‘partially emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases. (See Supplement 2, pp. 65-66; 68-70, for more extensive excerpts).

Source 16: Talmud Yerushalmi - Shabbat 14: 4: The דין רודף does not apply to the ‘partially emerged fetus’.

(See Supplement 1, Source 7b, p.55, for the commentary of the Pnei Moshe on the Yerushalmi).

| Rav Chisda asked, Can you save an adult [who is being pursued], by killing a child [pursuer]? Rav Yirmiya answered, Is this not addressed in the Mishnah (in Ohalot), “If *most of the fetus came out we cannot touch him because we may not push aside one life on account of another life?” Rav Yosse son of Rav Bon, quoting Rav Chisda said, That case [of the emerging fetus] is different because you do not know who is killing whom. | תלמוד ירושלמי שבת פרק יד, הלכה ד:

רַב חִסְדָּא בָּעֵי מַהוּ לְהַצִּיל נַפְשׁוֹ שֶׁל גָדוֹל בְּנַפְשׁוֹ שֶׁל קָטָן? הֲתִיב ר' יִרְמְיָה וְלָא מַתְנִי' הִיא, יָצָא רוּבּוֹ אֵין נוֹגְעִין בּוֹ שֶׁאֵין דּוֹחִין נֶפֶשׁ מִפְּנֵי נֶפֶשׁ? ר' יוֹסֶה בֵּי ר' בּוֹן בְּשֵׁם רַב חִסְדָּא שָׁנְיָיא הִיא תַּמָּן שֶׁאֵין אַתְּ יוֹדֵעַ מִי הוֹרֵג אֶת מִי. |

*This text of the Mishna in Ohalot differs from the version quoted in the Talmud Bavli (see Source 7, p. 8).

Figure 2: The ‘partially-emerged fetus’ case, as explained by Rav Moshe: The respective survivals of the fetus and mother are “inversely related”: If the active option is chosen (i.e., if the fetus is killed), the mother will live at expense of the fetus’ life. If the passive option is chosen, the fetus will be born while his mother will die. Therefore, the fetus and his mother pursue each other equally.

Green check: Denotes the saving of a life Red X: Denotes the loss of a life

Figure 3: The ‘fugitive with escape capability’ case, as explained by Rav Moshe: The respective survivals of the fugitive and townspeople are “inversely related”: If the active option is chosen (i.e., if the fugitive is handed over), the townspeople will live at the expense of fugitive’s life. If the passive option is chosen, the fugitive will escape and live while the townspeople will be killed. Therefore, the fugitive and the townspeople pursue each other equally.

Green check: Denotes the saving of a life Red X: Denotes the loss of a life

- However, this “flips” our original question (in paragraph 3, p. 14) “on its head". By his own definition of “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה”, how can Rav Moshe explain the permissibility to kill the ‘non-emerged fetus’ or to hand over the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ based on the דין רודף? Since all the obstructed labor and fugitive cases involve bidirectional רדיפה, we always have a “מאי חזית” dilemma and therefore, the דין רודף should not apply?

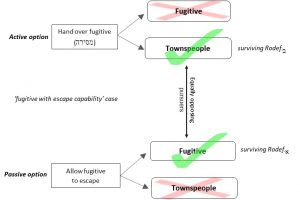

- Rav Moshe explains that in the ‘non-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive without escape capability’ cases, Rodef-א has a lower “level” of life than Rodef-בּ. In the ‘non-emerged fetus’ case, the fetus has an “incomplete נפשׁ” status whereas the mother has a “complete נפשׁ” status. Similarly, in the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ case, the fugitive only has transient life (חיי שׁעה, i.e., short stay of execution until the hooligans invade the city and kill everyone if the townspeople do not hand him over), while the townspeople have the potential for normal life expectancy (חיי עולם) if they hand him over. Therefore, we say that there is a “differential” (abbreviated with the symbol “D”) between the respective “life-levels” of Rodef-א and Rodef-בּ. Only Rodef-א pursues after this D and therefore, with respect to this D, only Rodef-א is a רודף. Since they are not equal pursuers (with respect to the D), Rodef-א is assigned the “definitive רודף” status and thus, there is no “מאי חזית” dilemma. Accordingly, the דין רודף will be applied to permit sacrificing the ‘non-emerged fetus’ or ‘fugitive without escape capability’ to save the mother or townspeople, respectively

Note: See Table 3, p. 21 and Figure 4, p. 22, for depiction of the “differential” (D) concept.

Note: The expression “definitive רודף” status, in reference to Rodef-א (the fetus or fugitive), is not intended to suggest that Rodef-א is considered more responsible (or a greater contributor) than Rodef-בּ for the perilous situation they are in. It is merely a convention that was created to refer to Rav Moshe’s explanation that Rodef-א alone pursues a “differential” between their “life levels”.

A. In the case of ‘non-emerged fetus’, only the fetus pursues after the נפשׁ-D between the complete נפשׁ of the mother and his own incomplete נפשׁ. Therefore, the fetus has the “definitive רודף” status and the דין רודף will permit killing him to save his mother. However, after the emergence of his head, since both the mother and the fetus have a complete נפשׁ, there is no נפשׁ-D between them. Therefore, they are equal רודפים and the דין רודף cannot be applied due to the “מאי חזית” logic (Source 17).

B. Similarly, in the case of the ‘fugitive without escape capability’, only the fugitive pursues after the life expectancy-D between the townspeople’s חיי עולם (normal life expectancy) and his own חיי שׁעה (transient life). Therefore, the fugitive has the “definitive רודף” status and the דין רודף will permit handing him over to save the townspeople (see Figure 5, p. 23, for a schematic diagram of the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ situation). However, if he can escape, since both the fugitive and the townspeople have potential for חיי עולם, there is no life expectancy-D between them. Therefore, they are equal רודפים and the דין רודף cannot be applied due to the “מאי חזית” logic (Source 18).

| However, [the ‘non-emerged’] fetus does not yet have a complete נפש, as we deduce from the fact that one does not incur capital liability (for killing an unborn fetus). Therefore, regarding the advantage (i.e., the נפש-D) that the mother has over the fetus – that she is a complete נפש while he is not yet a complete נפש – only the fetus is a רודף and his mother is not a רודפת (pursuer). Therefore, the דין רודף applies to the fetus because of the advantage that the mother has over him. | אגרות משה ,יורה דעה ח״ב, סימן ס׳, ענף ב׳:

אבל בעובר שעדיין אינו נפש גמור כדחזינן שאין נהרגין עליו, ונמצא שעל היתרון של האם מהעובר שהיא נפש גמור והוא אינו עדיין נפש גמור, הוי רק העובר רודף ואם אינה רודפת. לכן יש להעובר דין רודף מחמת היתרון זה שיש להאם עליו. |

Source 17: Rav Moshe’s explanation why the דין רודף applies to the ‘non-emerged fetus’ (See Supplement 2, pp. 65-66, 70-71):

Source 18: Rav Moshe’s explanation why the דין רודף applies to the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ (See Supplement 2, pp. 67, 69):

| However, if it is evident that everyone will die [including the fugitive, if they remain passive] ... the townspeople only pursue after the fugitive’s חיי שׁעה (transient life) while he pursuers after all their life (חיי עולם - normal life expectancy). Thus, regarding the essential life – which is the advantage (i.e., the life expectancy-D) that the townspeople have over the fugitive’s חיי שׁעה – the fugitive pursues after them while they do not pursue after him at all. Thus, the דין רודף applies to the fugitive despite his lack of intent to harm, since he nevertheless is the cause [of their impending danger]. | אגרות משה ,יורה דעה ח״ב, סימן ס׳, ענף ב׳:

אבל באם ברור שימותו כולם ... נמצא שהם רודפים אותו רק על חיי שעה והוא רודף אותם בכל חייהם. הרי נמצא שעל עיקר החיים שהוא היתרון מחיי שעה, הוא רודף אותם והם אינם רודפים אותו כלל, יש לו דין רודף אף שהוא שלא בכוונה כיון שעל כל פנים הוא הסבה. |

Table 3: Description of “differentials” between the participant’s respective “levels” of life in the ‘non-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive without escape capability’ cases

| Case | Participant | “Level” of life | Type of “differential” | Abbreviation for “differential” |

| ‘non-emerged fetus’ | Fetus | incomplete נפשׁ | נפשׁ-differential | נפשׁ-D |

| Mother | complete נפשׁ | |||

| ‘fugitive without escape capability’ | Fugitive | חיי שׁעה | life expectancy-differential | life expectancy-D |

| Townspeople | חיי עולם |

Figure 4: The “differential” (D) in the ‘non-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive without escape capability’ cases: The term “level” refers to “life-level”, either the “נפש-level” or the “life expectancy-level”. Rodef-בּ’s “Level 2” is higher than, and is inclusive of, Rodef-א’s “Level 1”. The D refers to the “differential” between “Level 1” and “Level 2”. Accordingly, only Rodef-א pursues after the D and therefore, he has the “definitive רודף" status.

| Case | Rodef-א | Rodef-בּ | ||

| Name | “Level 1” | Name | “Level 2” | |

| ‘non-emerged fetus’ | Fetus | incomplete נפש | Mother | complete נפש |

| ‘fugitive without escape capability’ | Fugitive | חיי שׁעה

transient life |

Townspeople | חיי עולם

normal life expectancy |

Figure 5: The ‘fugitive without escape capability’ case: If the active option is chosen (i.e., if the fugitive is handed over), the townspeople will live at the expense of the fugitive’s life. If the passive option is chosen, both the fugitive and townspeople will only have שׁעה חיי (temporary life extension). Since there is a life expectancy-D between the two “opposing parties”, they do not pursue each other equally.

Green check: Denotes the saving of a life Red X: Denotes the loss of a life

Combination check-and-X: Denotes the temporary extension of life

| Type of Situation | Sub- category | Who will be saved, as a consequence of choosing the ________ option? | Does 2Rodef-א pursue a D between the “life-levels” of Rodef-א and Rodef-בּ ? | 3Does ”משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” apply? | Who is assigned “definitive-רודף"

status? |

How does the Halacha decide?

which option? |

||

| 1Active | Passive | Yes/

No |

Explanation | |||||

| Obstructed labor | ‘non-emerged fetus’ | Mother’s complete נפש | Fetus’ incomplete נפש | Yes | The fetus pursues the D between the mother’s completeנפש and his own incomplete נפש. | No | Fetus | Active

(Feticide) |

| ‘partially- emerged fetus’ | Mother’s complete נפש | Fetus’ complete נפש | No | The fetus and mother pursue each other’s complete נפש. | Yes | No one | Passive | |

| Fugitive | ‘with escape capability’ | 4TP’s 5חיי עולם | Fugitive’s 6חיי שׁעה | Yes | The fugitive pursues the D between the TP’s חיי עולם and his own חיי שׁעה. | No | Fugitive | Active 7(מסירה) |

| ‘without escape capability’ | 4TP’s 5חיי עולם | Fugitive’s 5חיי עולם | No | The fugitive and TP pursue each other’s חיי עולם. | Yes | No one | Passive | |

Table 4: Summary of Approach # 2, (approach of Rav Moshe), to explain the different rulings in the obstructed labor and fugitive situations: Based on the position that an unintentional pursuer has a status of a רודף.

| Type of Situation | Sub- category | Who will be saved, as a consequence of choosing the ________ option? | Does 2Rodef-א pursue a D between the “life-levels” of Rodef-א and Rodef-בּ ? | 3Does ”משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” apply? | Who is assigned “definitive-רודף"

status? |

How does the Halacha decide?

which option? |

||

| 1Active | Passive | Yes/

No |

Explanation | |||||

| Obstructed labor | ‘non-emerged fetus’ | Mother’s complete נפש | Fetus’ incomplete נפש | Yes | The fetus pursues the D between the mother’s completeנפש and his own incomplete נפש. | No | Fetus | Active

(Feticide) |

| ‘partially- emerged fetus’ | Mother’s complete נפש | Fetus’ complete נפש | No | The fetus and mother pursue each other’s complete נפש. | Yes | No one | Passive | |

| Fugitive | ‘with escape capability’ | 4TP’s 5חיי עולם | Fugitive’s 5חיי עולם | No | The fugitive and TP pursue each other’s חיי עולם. | Yes | No one | Passive |

| ‘without escape capability’ | 4TP’s 5חיי עולם | Fugitive’s 6חיי שׁעה | Yes | The fugitive pursues the D between the TP’s חיי עולם and his own חיי שׁעה. | No | Fugitive | Active 7(מסירה) | |

1The active option is as follows: In the obstructed labor situation: feticide; in the fugitive situation: hand-over (מסירה).

2Rodef-א = fetus or fugitive; Rodef-בּ = fugitive or townspeople;

3For simplicity purposes, this can be regarded as synonymous with: “Is there a ‘מאי חזית’ dilemma?”.

4TP = Townspeople

5חיי עולם = Normal life expectancy; 6חיי שׁעה = Transient life (expectancy);

7ריש לקיש maintains that מסירה is only permitted if the hooligans imposed a “death sentence” (they have a grievance) against the ‘fugitive without escape capability’.VII. Application of אין דוחין נפשׁ מפני נפשׁ and the דין רודף to the multifetal pregnancy situation:

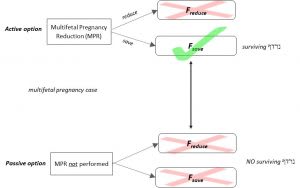

1. The following discussion refers to a hypothetical sextuplet pregnancy, in which:

A. There is a high probability of fatality for all fetuses either in utero or shortly after birth, if MPR is not performed. In this scenario, “Freduce” = the 3 fetuses that the physician wishes to reduce, and “Fsave” = the remaining 3 fetuses that the physician wishes to save.

B. All fetuses have the same potential to survive if other fetuses are reduced;

C. No fetus displays a gross abnormality or malformation (based on ultrasound imaging studies).

2. In light of the above discussions, several arguments can be made to either allow or prohibit MPR:

A. On one hand, perhaps the principle of אין דוחין would forbid performing MPR even though it would increase the survival probability of the remaining fetuses, since we would be forced to save some lives at the expense of others.

B. On the other hand, just as we are permitted to hand over the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ where everyone would die if the townspeople remained passive, perhaps we should be permitted to reduce some of the fetuses to save the others if all fetuses are otherwise likely to perish (without MPR). We have looked at two different approaches for the permissibility to hand over the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ (i.e., the permissibility for מסירה). The logic inherent in each of these approaches may also provide a basis to permit MPR.

i. Approach 1 - Chasdei Dovid: The permissibility for מסירה is based on the inapplicability of the “מאי חזית” logic. Since the fugitive will die whether or not the townspeople hand him over, the logic of “מאי חזית” does not apply.

ii. Approach 2 - Rav Moshe: The permissibility for מסירה is based on the דין רודף since the fugitive is considered a רודף after the townspeople.

C. Rabbi Dr. Zalman Levine (Reference 6) suggests that the “מאי חזית” logic may not apply in a MFP situation where there is a high risk of total fetal/neonatal death without reduction. Therefore, just as the inapplicability of the “מאי חזית” logic permits מסירה (when the fugitive is unable to escape, according to the Chasdei Dovid, Approach 1), this approach may also permit MPR.

D. According to Rav Moshe (Approach 2), perhaps each fetus in an MFP situation has the status of a רודף after the other fetuses. Just as the דין רודף permits מסירה (when the fugitive is unable to escape, according to Rav Moshe) despite the absence of volition to harm or wrongdoing, perhaps the דין רודף will permit MPR if the passive option is likely to lead to total fetal/neonatal death.

This approach is problematic, however, because Rav Moshe explains that the permissibility to hand over the ‘fugitive without escape capability’ is based on the fugitive being considered the “definitive רודף" due to the life expectancy-D between himself and townspeople. By MFP, there is no life expectancy-D between the fetuses, assuming all have the same survival probability. Accordingly, even if the fetuses are considered pursuers (רודפים), they all equally pursue after each other, and thus, we have a “מאי חזית” dilemma: “Why do you presume that that Freduce pursues after Fsave more than Fsave pursues after Freduce ?” Apparently, it does not seem possible for the דין רודף to permit MPR?

- In personal correspondence with Rabbi Dr. Zalman Levine (Reference 6), Rav Yosef Sholom Elyashiv ruled that the single deciding factor for permitting MPR is the probability of mortality for each of the fetuses. Rav Elyashiv permitted MPR (in a specific case presented to him by Rabbi Dr. Levine) if the probability of all fetuses perishing was greater than 50%. In addition, Rav Elyashiv ruled that major disability or morbidity (which is common in surviving multifetal-pregnancy babies) may not be considered a factor in allowing MPR.

- In Sefer Nishmat Avraham (Source 19), Rabbi Dr. Abraham records the ruling of Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach (henceforth referred to as “Rav Shlomo Zalman”) who permitted MPR in “cases where the pregnancy is at high risk” on the basis that “each of the fetuses has the status of a רודף”. I do not know the risk level necessary to be considered a “high risk” to the pregnancy, to permit MPR according to Rav Shlomo Zalman. Similarly, Rav Mordechai Eliyahu wrote that if all fetuses will otherwise die, each fetus is a רודף after the others and therefore, MPR would be permitted (Reference 11).

Source 19: Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach permits MPR in certain cases of high risk to the pregnancy based on the דין רודף; Sefer Nishmat Avraham. (See Supplement 1, Source 11, p. 58, for a more extensive excerpt).

| The Gaon, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, ZT”L, explained to me that in cases where the pregnancy is at high risk due to multiple fetuses, *each of the fetuses has the status of a רודף and therefore the physicians are permitted to select those fetuses for reduction whose termination will cause the least risk of aborting the entire pregnancy. He also agreed that this is permissible even beyond 40 days ..... The Gaon, Rav Yosef Sholom Elyashiv, Shlita, told me since the doctors state there is a risk in a quadruplet pregnancy that all the fetuses will be miscarried, it is permitted to reduce. On the other hand, it is known to me that the Gaon (Rav Elyashiv), Shlita, forbade reducing a triplet pregnancy. | נשמת אברהם חושן משפט סימן תכה:

הסביר לי הגאון זצ"ל שבמקרה של הריון בסיכון גבוה עקב ריבוי עוברים כל אחד מהעוברים יש לו דין של רודף ולכן מותר לרופא להרוג חלק מהם בזריקה בבחירת אותם לפי שיקול רופאי שהריגתם יגרום לסיכוי הקטן ביותר של הפלת כולם. והוא זצ"ל גם הסכים שמותר לעשות זאת אחרי ארבעים יום ....ואמר לי הגרי"ש אלישיב שליט"א שכיון שהרופאים אומרים שיש סכנה ברביעיה שתפיל את כולם, מותר לדלל. מאידך ידוע לי שהגאון שליט"א אסר דילול בשלישיה |

*If none of the fetuses displays abnormalities (which is our hypothetical case), the physician selects the fetus(es) to be reduced based on their position in the uterus (per Rabbi Dr. Levine, Reference 6). It is beyond my level of understanding to determine whether such a selection is Halachically equivalent to the designation required to permit מסירה in the fugitive case, or even if such equivalency would be necessary to permit MPR based on the דין רודף.

VIII. Possible approach to permitting MPR based on Rav Moshe’s explanation of the דין רודף:

Note: Rav Moshe has not published any ruling on the permissibility of MPR (possibly because this procedure was not yet clinically well established during his life time). Thus, any thoughts below are intended as merely an attempt to logically extend Rav Moshe’s Halachic analysis from the fugitive and obstructed labor situations discussed above, to multifetal pregnancy.

1. Rav Hershel Schachter (Reference 12) explains that the position of Rav Moshe, i.e., the prohibition of feticide is included under לא תרצח, is based upon the eventuality that a fetus would become a viable born person. Therefore, if the physicians state with near-certainty that all fetuses will die unless MPR is performed, since the eventuality of a viable born person does not exist, there would be no prohibition of לא תרצח. Therefore, MPR would be permitted to save the remaining fetuses in such cases. According to this approach, Rav Moshe would presumably not agree with Rav Elyashiv that a mortality risk of merely greater than 50% suffices to permit MPR. Rather, a much higher mortality risk would likely be required to permit MPR.

2. Above (VII-2-D, pp. 25-26), we suggested the possibility that perhaps Rav Moshe would consider each fetus as a רודף after the others and accordingly, the דין רודף would provide the basis for permitting MPR, which is the position of Rav Shlomo Zalman. However, we challenged this supposition: Since there is no life expectancy-D between fetuses, the “מאי חזית” logic (“Why do you presume that Freduce pursues after Fsave more than Fsave pursues after Freduce ?) would prevent the דין רודף from permitting MPR?

3. I would suggest that the key to determining whether the דין רודף can be applied to permit MPR is by assessing if the concept of “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” extends to the MFP If the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept applies to MFP, then, just as in the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases, we cannot apply the דין רודף and thus, MPR would be forbidden. Conversely, if the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept does not apply to MFP, the דין רודף could be applied and MPR would be permissible.

4. For purposes of simplicity, I suggest that Rav Moshe’s explanation how “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” applies in the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases, may be presented as follows: There are two ends of the “active-vs.-passive option spectrum” (abbreviated as “A-vs.-P spectrum”): The “passive end” and the “active end”. At the “passive end”, Rodef-א (the fetus or fugitive) will live at the expense of Rodef-בּ (the mother or townspeople); whereas, at the “active end”, Rodef-בּ will live at expense of the Rodef-א (see Figures 2-3, pp. 18-19). Since we see that their respective survivals are inversely related, it is evident that Heaven has arranged that Rodef-א and Rodef-בּ are equally “opposing רודפים”. Accordingly, we have no basis to assign the “definitive רודף” status to one party more than to the other and thus, the דין רודף cannot be applied.

5. How does this help us determine if “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” applies to the MFP situation? Two opposing perspectives are suggested, to either support or oppose applying “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” to

A. On one hand, there are two analogies between the MFP situation and the ‘fugitive with escape capability’ case: (1) Each fetus in the MFP situation has a similar potential to survive if other fetuses are reduced, and thus, there is no life expectancy-D between the fetuses; (2) Since Fsave can only live if Freduce is reduced and visa versa, therefore, the respective survivals of all the fetuses are inversely related. From this vantage point, we should say that all fetuses pursue after each other equally. Accordingly, just as in the ‘fugitive with escape capability’ case, “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” should apply and theדין רודף would not apply to permit MPR.

B. On the other hand, a strong argument could be made against applying “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” to MFP, as follows: At the “passive end” of the “A-vs.-P spectrum” (i.e., if MPR is not performed), no fetus is likely to live at the expense of another fetal life since there is a high risk of total fetal/neonatal death. Only at the “active end” (i.e., if MPR is performed), some fetuses (i.e., Fsave ) will live at the expense of the others (i.e., Freduce ) (see Figure 6, p. 31). Accordingly, the survivals of Fsave and Freduce are not truly inversely related in the same manner as in the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases. Therefore, we would not say that Heaven has arranged that all parties pursue each other equally. Accordingly, “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” would not apply to the MFP situation in question and theדין רודף could permit MPR despite the absence of a life expectancy-D.

6. Thus, we have arguments both to support and oppose applying “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” to the MFP situation. I would like to suggest the following approach why “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” should not apply to the MFP situation and thus, theדין רודף would permit MPR.

A. In the חידושי רבינו חיים הלוי על הרמב”ם (Reference 8), Rav Chaim states, “The רמב״ם understands that the תורה’s authorization for killing the רודף is based on the imperative of saving the life of the pursued party (הצלת הנרדף).” In the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases, whether we choose the active option or passive option, we will save the life of a נרדף since each רודף is simultaneously also a נרדף. If we choose the passive option, Rodef-א (the fetus or fugitive) is the נרדף who will be saved and if choose the active option, Rodef-בּ (the mother or townspeople) is the נרדף who will be saved. Since the entire purpose of theדין רודף is to save the נרדף, unless we know that one of the “opposing parties” has the “definitive רודף” status, we should choose the passive option since we are saving a נרדף without actively taking a life. This would seem to fit with Rav Moshe’s explanation of “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה”: The same Heavenly process that caused the mother (Rodef-בּ) to be the object of the fetus’ (Rodef-א’s) pursuit, i.e., that she would suffer such a difficult labor that she cannot live if the fetus’ life is spared, has also caused the fetus to become the object of the mother’s pursuit. Since the fetus is an equal נרדף as the mother is, there is just as much imperative to save his life as there is to save his mother’s life. The “מאי חזית” logic, therefore, dictates that we choose the option of saving a נרדף which would not require actively taking a life. Only if we know that Rodef-א is the “definitive רודף” (in the ‘non-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive without escape capability’ cases), which is another way of saying Rodef-בּ is the “definitive נרדף”, the imperative of saving Rodef-בּ determines that we must choose the active option.

B. However, in the MFP situation, there is only one option that would result in saving a נרדף, i.e., the active option (MPR). The passive option is not likely to save any lives. Therefore, the imperative of saving the life of a נרדף should determine that we choose the active option, i.e., we should perform MPR to save some of the fetuses.

7. Rav Moshe’s use of the “מאי חזית” terminology in the context of the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases, may be analogous to רש״י’s understanding of the “מאי חזית” logic in the “coerced murder” case.

A. Rav Moshe portrayed רש״י’s view of the “מאי חזית” logic in the “coerced murder” case as “two negative consequences vs. one negative consequence” (Figure 1, p. 5).

B. Similarly, in the ‘partially-emerged fetus’ and ‘fugitive with escape capability’ cases, we have a “standoff” between two options:

i. If we choose the passive option, there will be one positive consequence, הצלת הנרדף (saving the pursued party), without performing an act of שׁפיכת דמים (murder).

ii. If we choose the active option, there will be a positive consequence, הצלת הנרדף, but there will also be a negative consequence, an act of שׁפיכת דמים.

C. Thus, we have a “standoff” between: (1) the passive option, which will only produce a positive consequence; vs. (2) the active option, which will produce both a positive and a negative consequence. Therefore, the “מאי חזית” logic dictates that we should choose the passive option which will only produce a positive consequence.

8. However, in the MFP situation, there is no similar “standoff” since the passive option will not likely produce any positive consequence. The only available option which will produce the positive consequence of הצלת הנרדף is the active option, i.e., performing MPR. Therefore, the “מאי חזית” logic and thus, the “משׁמיא קא רדפי לה” concept, will not apply and theדין רודף would permit MPR. The only remaining question is which fetus(es) to select for reduction. Perhaps this is not a question in Halacha, but rather, a strategic medical question, i.e., which fetuses does the physician believe he can reduce while causing the least risk to the remainder of the fetuses as Rav Shlomo Zalman said (Source 19, p. 26).